Tag Archives: libertinism

A Nymphaeum and a Temple to Venus in an Eighteenth-Century English Garden

The Temple of Venus was one of the earliest features of West Wycombe’s gardens, which Sir Francis Dashwood began designing in the 1740s. It is a round temple, perched on a small hill. Below it was a section of the garden, known as Venus’ Parlor, which was cleared when Humphrey Repton re-landscaped West Wycombe beginning in 1796. As a consequence, Dashwood’s baroque figurative program for this section of the garden was destroyed. However, from remaining evidence, we can piece together what it looked like.

A view by William Hannan from the 1750s portrays the temple as it originally looked.

On a manmade hill, a circular temple – an allusion to the rotunda at Stowe but situated in gardens with a very different moral program – housed a copy of the Venus de Medici. A path led down the hill to a grotto built underneath the temple. A design for the grotto still exists in the Dashwood collections.

It appears that this section of the garden followed the design of a nymphaeum similar to those found in the gardens of Renaissance Italian villas. In effect, it is similar to Palladio’s nymphaeum for the Villa Barbara, although on a much smaller scale.

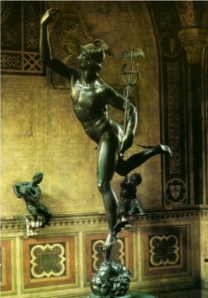

The oval entrance to the grotto alluded playfully to sexuality and temptation, with symbols that all but the most obtuse visitor could understand. Perched above the “door of life” – as John Wilkes later referred to it, was a lead copy of Giambologna’s sixteenth-century Mercurio – an iconic figure throughout the early modern period.[1] The lead Mercury can be seen in Hannan’s view. While Mercury’s association with commerce and communication are well known, eighteenth-century libertines often associated Mercury with sexual commerce as well.

While few textual descriptions of the site exist – and those that do are dubious descriptions – the tone of the site is embodied in John Wilkes’s description of West Wycombe. In 1763, he wrote that “you find at first what is called an error in limine; for the entrance to it is the same entrance by which we all come into the world, and the door is what some idle wits have called the door of life.”[2] He continued that Lord Bute had encouraged Dashwood to erect a Paphian column – a reference to the Temple of Venus at Paphos on Cyprus – in front of the entrance:

While few textual descriptions of the site exist – and those that do are dubious descriptions – the tone of the site is embodied in John Wilkes’s description of West Wycombe. In 1763, he wrote that “you find at first what is called an error in limine; for the entrance to it is the same entrance by which we all come into the world, and the door is what some idle wits have called the door of life.”[2] He continued that Lord Bute had encouraged Dashwood to erect a Paphian column – a reference to the Temple of Venus at Paphos on Cyprus – in front of the entrance:

There are in these gardens no busts of Socrates, Epaminondas, or Hampden [a reference to the Temple of Ancient Virtue and the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe]; but there is a most indecent statue of the unnatural satyr [the famed Satyr with a Goat in the King of Naples’ collection]; but at the temple I have mentioned, are two urns sacred to the Ephesian matron, and to Potiphar’s wife, with the inscriptions Matronae Ephesiae Cineres, Dominae Potiphar Cineres.[3]

The reference to the Ephesian matron was from Petronius’ Satyricon in which the chaste Matron Ephesia despairs at her husbands death and begins to starve herself in his tomb. Eventually, she is seduced by a soldier who brings her food. Potiphar’s wife was the woman who attempted to seduce Joseph in the biblical story. Thus, two of the most “sacred” items in the gardens were models of female infidelity.

It is no surprise that Repton cleared the site of its most explicit references to sexuality, libertinism, and anti-virtue in 1796. Likewise, it is perhaps not surprising that Dashwood’s descendants would commission a replica of the original grotto in the 1980s. By this time, West Wycombe had become an important National Trust Property – not only because of its architecture, but because of the ability of its illicit history to draw visitors. In 1982, Quinlan Terry completed his reconstruction of the grotto and temple for Sir Francis Dashwood. This commission was part of an overall plan to re-infuse the landscapes of West Wycombe with references to the world of the Hellfire Club, a draw for tourists which was meant to raise both the profile and income of the estate.

Citation: Jason M. Kelly, “A Nymphaeum and a Temple to Venus in an Eighteenth-Century English Garden,” Secrets of the Hellfire Club Blog (8 March 2012), https://hellfiresecrets.wordpress.com/2012/03/08/a-nymphaeum-and-a-temple-to-venus-in-an-eighteenth-century-english-garden/.

[1] Not only did Giambologna produce several copies himself (Museo del Bargello, Florence; Villa Medici, Rome; Museo Nazionale, Naples originally in Farnese collection; Kunsthistorisches, Vienna), but collectors such as Sir Hans Sloane and Lawrence Dundas added copies to their own collections. See, for example, Johann Zoffany’s Lawrence Dundas and Grandson in the Zetland Collection and Jeremy Warren, “Sir Hans Sloane as a Collector of Small Sculpture,” Apollo (2004): 8.

[2] New Foundling Hospital for Wit, vol. 3 (London, 1784), p. 78.

[3] New Foundling Hospital for Wit, vol. 3 (London, 1784), p.

![[Anonymous]. Venus’ Parlor. ca. 1740s. Courtesy of Sir Edward Dashwood [Anonymous]. Venus’ Parlor. ca. 1740s. Courtesy of Sir Edward Dashwood](https://hellfiresecrets.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/grotto.png?w=490&h=354)