Category Archives: History

Ghosts, Satanism, and 19th-Century Tourism at West Wycombe

Decades after the group ceased to meet, the stories of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey circulated in the form of rumors and gossip. And, as members of the club passed away, popular interest remained. At the turn of the nineteenth century, tourism in Britain increased, and West Wycombe became a popular destination. Not only was curiosity piqued by the famed gardens and walks of the Monks, but rumors of hauntings also fueled interest.

From Earth to Heaven. Music [for four voices] Performed at the Ceremony of Depositing the Heart of the late Paul Whitehead in the Mausoleum at HighWycombe, etc. [London, 1784]

Locals soon saw the potential for profit. They led tourists to the supposed meeting sites of the Medmenham Monks – the ball at the top of the St. Lawrence Church and the West Wycombe caves, chalk tunnels which Dashwood had excavated in the 1750s to employ the local population. They told the tourists ghost stories. Visitors were even given the opportunity to hold Paul Whitehead’s heart — until it was stolen by an unnamed Australian in 1829.[2] The ghost stories became more and more popular in the nineteenth century. For example, in the 1870s, Mortimer Collins wrote that Medmenham was

Right famous for a veritable ghost;

The hell-fire club at Med’nam turn’d men pale;[3]

Although he decided not to tour the caves in the 1870s, Mortimer Collins noted that any visit to the St Laurence Church of West Wycombe entailed visiting the caves, passing “an hour or two in dirt and darkness,” “the victim of a guide.”[4] Another author noted that he toured the caves in 1875, and on this visit, he also visited the golden ball at the top of the church, now covered with the autographs of visitors. He was charged 6 pence for an entry fee, and it was so popular that it brought the church £120 revenue per annum – in other words, about 4800 visitors every year.[5]

The local tour guides, who received tips from the visitors, must have been telling and retelling the story of the Monks of Medmenham with some consistency, for the stories about West Wycombe tended to be fairly consistent. Most authors noted that while the monks’ sexual appetites were excessive – and that the men had poor morality – they were not abnormal for the eighteenth century.[6] One Oxford student remembered them thus:

In Medmenham Abby they passed the day,

Those jolly Abbots, ‘mid wine and lay:

There Hugh le Despencer, gallant and free,

Bid “fay ce que voudras” their motto be.[7]

Likewise, the men were generally represented as areligious, or agnostic, not openly atheistic.[8] The story of Whitehead and Dashwood’s romantic relationship had disappeared, even though the story had been printed with every edition of William Cowper Works during the first half of the nineteenth century. And, as they had been in the 1750s, the monks and their world were a source of curiosity. They had become part of the community’s imaginary landscape – part of its heritage – a set of stories and attractions that brought visitors to a small Georgian town along the road to Oxford.

Then, within just a few years at the turn of the 20th century, the stories about the West Wycombe landscape changed. They became more terrifying, and the topography of West Wycombe became potentially threatening. In 1894, Charles Henry Pearson made the first reference to satanic rituals at West Wycombe:

The worst acts imputed to the monks of Medmenham are, I believe, the invocation of the devil by Lord Sandwich, [and] the giving [of] the sacrament to a dog by the same worthy.[9]

In 1901, another author claimed that Medmenham was haunted by the blasphemous monks, who indulged in “beastly pleasures and beastly humors.” [10] Another author claimed that “the wraith of the last of the mad monks of Medmenham” haunted the landscape as a “homicidal ghost.”[11] Who started these more threatening versions of the area’s history is unknown, but one contemporary claimed that they were being circulated by “local mystery-mongers.”[12]

It seems that the new stories at West Wycombe and Medmenham did nevertheless contribute to the local tourist economy. And, one writer from the Times recognized the value of the mysteries and secrets of West Wycombe in an analysis in 1920:

The oldest of us never loses that part of youth which sees romance in sheer villainy. We disapprove for righteousness’ sake, but such a motto as – “Fay ce que voudras” – the very text of hedonism charms reputable persons into curiosity and ever into a shame faced sympathy . . . No one knows accurately what were the revels in this mysterious place. The proceedings were secret, but rumour said that wild rites were practiced. Satan received the crapulent homage of the pseudo-monks.[13]

While the church and caves were consistent tourist attractions in the 1920s – and, in fact, the ghost of Paul Whitehead had been joined by Sukie, the ghost of a murdered, love-scorned chambermaid from the George and Dragon Inn – the rest of the village struggled financially.[14] To save the pristine village, which Victorian aesthetics had left virtually untouched, the Royal Society of Arts, Commerce, and Manufacture purchased it in March 1929.[15] Transferring the title to the National Trust in 1934 was followed by Sir John Dashwood’s grant of the church hill and the caves in 1935 and 300 acres and an endowment in 1943.[16] The postwar years escalated the mythmaking at West Wycombe, and stories of poltergeists and villainous monks found their way into an increasingly broad array of popular culture.

[1] William Copwer to Rev. William Unwin, 24 November 1781, Works of William Cowper, vol. 2 (London, 1853), pp. 373-4.

[2] West Wycombe Park, The Dashwood Mausolem [n.d.], p. 8.

[3] Collins to T.E. Kebbel, 13 September 1872, Mortimer Collins, Mortimer Collins, His Letters and Friendships with Some Account of His Life, vol. 1, ed. Frances Collins (London, 1877), p. 113.

[4] Mortimer Collins, Pen Sketches by a Vanished Hand: From the Papers of the Late Mortimer Collins, ed. Tom Taylor (London: Richard Bentley, 1879), p. 101.

[5] Edward Verrall Lucas, Pleasure Trove (Books for Libraries Press, 1968), p. 123.

[6] Alfred Rimmer, Rambles Round Eton & Harrow, new ed. (London: Chatto & Windus, 1898), pp. 36-43.

[7] “On the Thames: A Summer Idyll,” College Rhymes, vol. 7 (Oxford, 1866), p. 147.

[8] Cf. Edward Walford, Tales of Our Great Families, vol. 2 (London, 1877), pp. 187-8.

[9] Charles Henry Pearson, National Life and Character: A Forecast (London: Macmillan, 1894), pp. 211-12 fn. 3.

[10] Justin McCarthy, History of the Four Georges, vol. 3 (New York, 1901).

[11] Eliakim Littell and Robert S. Littell, The Living Age, 7th series, vol. 18 (1903), p. 420.

[12] Charles George Harper, The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road (1905), p. 120.

[13] Times, 29 March 1920, no. 42371, p. 17, col. f.

[14] The caves were drawing thousands of visitors even in the midst of the depression in 1935. See Times, 23 July 1935, no. 47123, p. 11, col. e. Supposedly, Sir Francis Dashwood had a secret passage between the house and the George and Dragon, which the locals claimed to have partially excavated in 1963. See Times, 11 June 1963, no. 55724, p. 7, col. f.

[15] Times, 6 February 1934, no. 46671, p. 11, col. d.

[16] Times, 23 July 1935, no. 47123, p. 11, col. e; Times, 23 December 1943, no. 49736, p. 7, col. b.

Pop Culture and Medmenham

As those of you who follow this blog know, it’s been inactive for a while. This is because I took a new position at my university and haven’t had time to do the necessary research. One of the things that I have been working on is adding pop culture references to Dashwood, Medmenham, the Hellfire Club, etc. to my research folder. This is because I think the afterlife (a.k.a. memory) of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey is as interesting and important as their existence during the 1740s through the 1760s. Many of you probably know a number of these references, which include The Avengers, the X-Men, Ghost Hunters, and more.

As those of you who follow this blog know, it’s been inactive for a while. This is because I took a new position at my university and haven’t had time to do the necessary research. One of the things that I have been working on is adding pop culture references to Dashwood, Medmenham, the Hellfire Club, etc. to my research folder. This is because I think the afterlife (a.k.a. memory) of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey is as interesting and important as their existence during the 1740s through the 1760s. Many of you probably know a number of these references, which include The Avengers, the X-Men, Ghost Hunters, and more.

As I have been collecting these references, I have been thinking that it might be useful to create a master list and add it to the blog. And, I was hoping that you might help me. In the comments section below or on the Facebook page, would you post any pop culture references to Medmenham and the Hellfire club that you know? These could include music, theater, film, art, or even Hellfire themed restaurants. If you have any ephemera that might be interesting, please provide links to images. I will of course cite you as co-contributors to the blog post when I put the master list together.

To get us started, here is a clip from The Hellfire Club (Regal Films, 1961). If you haven’t seen it, I wouldn’t say that you’re missing much, but it has great visual references to the histories (real and imagined) of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey. Check out the baboon skull embedded in the cave walls in the opening sequence.

The Public Reputation of the Medmenham Monks

How much did the London public know about the existence of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey during the 1750s and early 1760s? It is clear that its members had little reticence about publicizing their activities or worry about gossip and rumor. I have already posted about Francis Dashwood’s penchant for dressing up as monks and commissioning satirical religious portraits of himself (https://hellfiresecrets.wordpress.com/2012/03/02/francis-dashwood-portraiture-and-the-origins-of-the-hellfire-club/). It seems that he and his fellow members took great pleasure in encouraging gossip about their “secret” society.

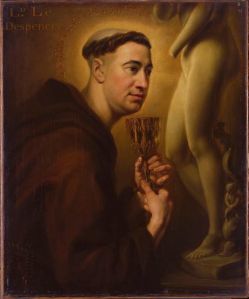

In one instance, Dashwood used his association with the Society of Dilettanti to publicize the group of “monks.” The Dilettanti required its members to present portraits of themselves to be hung in their meeting room, and the painter to the Dilettanti, George Knapton, painted Dashwood as “SAN FRANCESCO DE WYCOMBO” in 1742. Importantly, the Dilettanti’s meeting room was in a public tavern, and tavern-goers had access to it. In effect, the space became an informal art gallery. Because of this, a larger population came into regular contact with Dashwood’s image as St. Francis of Wycombe. The consequences of continuous public contact with Dashwood’s painting were described by John Wilkes. He said of Dashwood’s portrait, which had continuously hung at the King’s Arms from 1742 to 1757 before it was transferred to the society’s new home at the Star and Garter:[1]

In one instance, Dashwood used his association with the Society of Dilettanti to publicize the group of “monks.” The Dilettanti required its members to present portraits of themselves to be hung in their meeting room, and the painter to the Dilettanti, George Knapton, painted Dashwood as “SAN FRANCESCO DE WYCOMBO” in 1742. Importantly, the Dilettanti’s meeting room was in a public tavern, and tavern-goers had access to it. In effect, the space became an informal art gallery. Because of this, a larger population came into regular contact with Dashwood’s image as St. Francis of Wycombe. The consequences of continuous public contact with Dashwood’s painting were described by John Wilkes. He said of Dashwood’s portrait, which had continuously hung at the King’s Arms from 1742 to 1757 before it was transferred to the society’s new home at the Star and Garter:[1]

There was for many years in the great room, at the king’s arms tavern, in Old Palaceyard, an original picture of Sir Francis Dashwood, presented by himself to the Dilettanti club. He is in the habit of a Franciscan, kneeling before the Venus of Medicis, his gloating eyes fix’d, as in a trance, on what the modesty of nature seems most desirous to conceal, and a bumper in his hand, with the words MATRI SANCTORUM in capitals. The glory too, which till then had only encircled the sacred heads of our Saviour and the Apostles, is made to beam on that favourite spot, and seems to pierce the hallow’d gloom of maidenhead thicket. The public saw, and were for many years offended with so infamous a picture, yet it remain’d there, till that club left the house.[2]

Consequently, the lascivious and anti-religious connotations of this painting caused Londoners to confuse the activities of the Dilettanti with the private lives of its members. Even Horace Walpole, typically “in-the-know,” succumbed to conflating the Dilettanti and the “Order of St. Francis,” writing that Dashwood’s club was a “more select order” of Dilettanti:

These pictures were long exhibited in their club room in Palace Yard; but of later years St. Francis had instituted a more select order. He and some chosen friends had hired the ruins of Medmenham Abbey near Marlow.[3]

This confusion persisted throughout the 1760s and did much to link the Society of Dilettanti’s reputation to the Monks of Medmenham Abbey.

It seems that the “monks” of the Order of St. Francis were both cavalier about their activities and took pleasure in the notoriety – good and bad – that their excesses garnered. For example, Paul Whitehead’s membership in the Medmemnham Monks is one of the reasons that Boswell gives for Samuel Johnson’s dislike of the poet.[4] In 1762, John Wilkes was proud to claim that he had slighted (for a second time) William, Lord Talbot by postponing their duel because of a hangover that he had incurred at Medmenham. Writing to Richard Grenville, Earl Temple, on 6 October, the day after the duel actually took place, Wilkes wrote about his sarcastic exchange with Talbot.

I was come from Medmenham Abbey where the jovial monks of St. Francis had kept me up till four in the morning, that the world would therefore conclude I was drunk, and form no favourable opinion of his lordship from a duel at such a time.[5]

Temple’s response suggests familiarity with the group and that Wilkes’s behavior in this incident was a confirmation of his masculinity: “Firmness, coolness, and a manly politeness, makes up the whole of this transaction on your part . . . I was sure you would extricate yourself like a man.”[6]

Adapted from Jason M. Kelly, The Society of Dilettanti: Archaeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2009), chapter 2.

[1] The Society moved their room to the Star and Garter Tavern in May 1757. See SDSM, 1 May 1757.

[2] Reprinted in A Select Collection of the Most Interesting Letters on the Government, Liberty, and Constitution of England, vol. 2 (London, 1763), p. 37. This was an extension of [John Wilkes], Public Advertiser (2 June 2 1763).

[3] Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of King George III, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), p. 114.

[4] James Boswell, Life of Johnson, ed. R.W. Chapman (Oxford, 1980), p. 91.

[5] Wilkes to Temple, 6 October 1762 in Letters between Duke of Grafton . . . and John Wilkes, vol. 1 (London, 1769), pp. 22-3.

[6] Temple to Wilkes, 6 October 1762, Grenville Papers, vol. 1, p. 478.

The Education of an Eighteenth-Century Squire: John Wilkes (1725-1797)

Much of the knowledge that we have of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey derives from the scandals and political debates surrounding John Wilkes, who was a key proponent of political reform in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. It is easy to overlook Wilkes’s education in a rush to explore the controversies of the 1760s and 1770s. However, the nature of Wilkes’s education provides insight into the intellectual milieu of the Hellfire Club.

Much of the knowledge that we have of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey derives from the scandals and political debates surrounding John Wilkes, who was a key proponent of political reform in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. It is easy to overlook Wilkes’s education in a rush to explore the controversies of the 1760s and 1770s. However, the nature of Wilkes’s education provides insight into the intellectual milieu of the Hellfire Club.

Wilkes was the son of an Anglican brewer, but his education seems to have been controlled by his Presbyterian mother. In 1734, she sent John and his two brothers to study with the Presbyterian schoolmaster John Worsley.[1] His father eventually had him study with Matthew Leeson, a Presbyterian minister, who abandoned his church at the age of 60 during a crisis of conscience that led him to embrace the Arian creed.[2]

In 1742, Wilkes entered Lincoln’s Inn, one of the four Inns of Court, to study law. He was fifteen years old at the time. It was clear that the boy did not want to become a lawyer, but entering the Inns of Court gave him access to court circles and was one way that the son of a middling brewer could expand his social network and advance his status.

Wilkes, accompanied by Leeson and another student named Hungerford Bland, enrolled in the University of Leiden in 1744. Leiden was a haven for Dissenters who could not enter Oxford of Cambridge. The young man made many friends there, including Alexander Carlyle. Carlyle recorded that Wilkes’s tutor, Matthew Leeson, was “an old ignorant pedant” who was a poor educator.[3] And, it seems that he did little to control Wilkes’s activities. The ability to break away from the strictures of rural life in England led the eighteen-year-old to a debauched lifestyle. Wilkes recounted his life at Leiden to James Boswell in Naples in 1765:

At school and college I never read; always among women a Leyden. My father gave me as much money as I pleased. Three or four whores; drunk every night. Sore head morning, then read. I’m capable to sit thirty hours over a table to study.[4]

Nevertheless, it is clear that Wilkes was a scholar – an independent one at that. This caused consternation to his tutor Leeson. As Carlyle later reported, Leeson’s

chief object seemed to be to make Wilkes an Arian also, and he teased him so much about it that he was obliged to declare that he did not believe the Bible at all, which produced a quarrel between them, and Wilkes, for refuge, went frequently to Utrecht, where he met with Immateriality [Andrew] Baxter, as he was called, who then attended [Walter Stuart, 8th] Lord Blantyre and Mr [William] Hay of Drummellier, as he had formerly done Lord John Gray.

Abandoning Christian theology, Wilkes looked for other men who would join him in philosophical inquiry. These individuals included Andrew Baxter (1686/7–1750). Baxter and Wilkes became close friends – perhaps even lovers – and Wilkes looked to the older man as a substitute tutor.[5] Baxter was a Newtonian and supporter of Samuel Clarke against the criticisms of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his followers.[6] He engaged Wilkes in debates over natural philosophy and metaphysics. The two men held long, speculative conversations, evidenced in Baxter’s dedication of his final work to Wilkes.[7] In 1747 in an unpublished dialogue defending Newtonianism, Baxter even based his main character, Histor, on Wilkes.[8]

Abandoning Christian theology, Wilkes looked for other men who would join him in philosophical inquiry. These individuals included Andrew Baxter (1686/7–1750). Baxter and Wilkes became close friends – perhaps even lovers – and Wilkes looked to the older man as a substitute tutor.[5] Baxter was a Newtonian and supporter of Samuel Clarke against the criticisms of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his followers.[6] He engaged Wilkes in debates over natural philosophy and metaphysics. The two men held long, speculative conversations, evidenced in Baxter’s dedication of his final work to Wilkes.[7] In 1747 in an unpublished dialogue defending Newtonianism, Baxter even based his main character, Histor, on Wilkes.[8]

From his association with Baxter, it is clear that Wilkes was reading some of the works of the great philosophers of his age. And, his knowledge of the Newtonians and Leibniz and his followers was probably quite extensive. But, Wilkes pursued studies beyond what Baxter encouraged. In 1745, Wilkes presented an English translation of the works of Spinoza to Baxter.[9] Spinoza (1632-77), the central thinker of the radical Enlightenment, was decried by both moderate and traditionalist segments of the intelligentsia, who labeled him an atheist who threatened to erode the moral foundations of society.[10]

Wilkes and Baxter cultivated their friendship among a circle of Britons who formed a club, based in Leiden. They met three times a week, most often at members’ lodgings at the boarding house of Mademoiselle Van der Tasse, but sometimes at the home Mr. Gowans, a Scottish clergyman. They “drank coffee, and smoked tobacco, and chatted about politics, and drank claret, and supped on bukkam (Dutch red-herrings), and eggs, and salad, and never sat later than twelve o’clock–at Mr Gowan’s, the clergyman, never later than ten, unless when we deceived him by making such a noise when the hour was ringing as prevented his hearing it.”[11] At Mademoiselle Van der Tasse’s house, the coffee was the best in the city and a small bottle of claret cost only a shilling. Alexander Carlyle described her and the house as follows.

Vandertasse’s was an established lodging-house, her father and mother having carried on that business, so that we lived very well there at a moderate rate — that is sixteen stivers for dinner, two for coffee, six for supper and for breakfast. She was a lively little Frenchwoman, about thirty-six, had been tolerably well-looking, and was plump and in good condition. As she had only one maid-servant, and five gentlemen to provide for, she led an active and laborious life; insomuch that she had but little time for her toilet, except in the article of the coif, which no Frenchwoman omits. But on Sundays, when she had leisure to dress herself for the French Church, either in the morning or evening, then who but Mademoiselle Vandertasse! She spoke English perfectly well, as the guests of the house had been mostly British.[12]

The members of the group who met at Van der Tasse’s made up about half of the roughly 22 British students in Leiden according to Alexander Carlyle’s estimate.[13] They included the poet Mark Akenside and his lifetime companion, Jeremiah Dyson; Hungerford Bland; the Greek scholar, Anthony Askew; John Campbell, Jr. of Stonefield with his tutor Professor Morton of St. Andrews; Alexander Carlyle; William Dowdeswell, later Chancellor of the Exchequer; John Freeman of Jamaica; John Gregory, afterwards a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Aberdeen and a doctor in Edinburgh; James Johnstone, later 3rd Bt. of Westerhall, Dumfries; Charles Townshend, later Chancellor of the Exchequer; and John Wilkes. Those peripheral to this club were Mr Wetherell of the West Indies; Dr. Charles Congalton; a Mr. Keefe of Ireland; Willie Gordon, later KB; Dr. Dickson; and Nicholas Monckly, according to Carlyle, “an ignorant vain block-head”; and a Mr. Skirrat.[14]

Most importantly for Wilkes was a foreign member of the club, Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d’Holbach (1723-89), who arrived in Leiden in 1744. It is unclear to what extent d’Holbach influenced Wilkes or vice versa. D’Holbach was not yet the atheistic materialist that he would be in the following decade. But, their membership in the club pointed to the freethinking radicalism of the circle. D’Holbach and Wilkes remained close friends for life, and the budding philosopher was emotionally wrought when Wilkes left Leiden to return to England: “I need not tell you the sorrow our parting gave me, in vain Philosophy cried aloud nature was still stronger and the philosopher was forced to yield to the friend, even now I feel the wound is not cur’d.”[15] Wilkes was his closest intellectual companion, and d’Holbach wrote to Wilkes that “I want in this country a true bosom friend like my dear Wilkes to converse with, but my pretenssions [sic] are too high, for every abode with such a company would be heaven for me.”[16]

Most importantly for Wilkes was a foreign member of the club, Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d’Holbach (1723-89), who arrived in Leiden in 1744. It is unclear to what extent d’Holbach influenced Wilkes or vice versa. D’Holbach was not yet the atheistic materialist that he would be in the following decade. But, their membership in the club pointed to the freethinking radicalism of the circle. D’Holbach and Wilkes remained close friends for life, and the budding philosopher was emotionally wrought when Wilkes left Leiden to return to England: “I need not tell you the sorrow our parting gave me, in vain Philosophy cried aloud nature was still stronger and the philosopher was forced to yield to the friend, even now I feel the wound is not cur’d.”[15] Wilkes was his closest intellectual companion, and d’Holbach wrote to Wilkes that “I want in this country a true bosom friend like my dear Wilkes to converse with, but my pretenssions [sic] are too high, for every abode with such a company would be heaven for me.”[16]

The importance of the intellectual circle at Leiden shaped all of the young gentleman to greater and lesser degrees. For both d’Holbach and Wilkes, sociability and clubability defined their public lives. When he settled in Paris, d’Holbach held twice-weekly meetings at his house on rue Royale Saint-Roche (now 8 rue des Moulins) – a center of philosophical radicalism from the 1750s through the 1780s. When he became an outlaw in 1763, partly because of his activities at West Wycombe, Wilkes eventually went to stay with d’Holbach and attend the salon. For his part, Wilkes became central to a number of coteries, including the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks (1754) and, of course, the Monks of Medmenham Abbey. Not surprisingly, several of his friends from Leiden joined him as friars.

In some ways, John Wilkes’s education was not uncommon for a middling child of a Dissenter household. He had a number of tutors, studied at the Inns of Court, and went abroad to university where he never took a degree. What made Wilkes’s education unique came as a result not of his education, but as a consequence of the sociable world of the continent. As it happened, he fell into a group of exceptional individuals – both politically minded and philosophically freethinking. To what extent Baxter, d’Holbach, or Spinoza each influenced him is impossible to gauge because many of his papers were burned by his daughter Polly. However, the radicalism of each of them and Wilkes’s own desire to push himself intellectually no doubt shaped his outlook on the world – to the extent that his notion of mores were less dominated by Christian theology and his politics were more egalitarian than many of his contemporaries.

Citation: Jason M. Kelly, “The Education of an Eighteenth-Century Squire: John Wilkes (1725-1797),” Secrets of the Hellfire Club Blog (25 March 2012), https://hellfiresecrets.wordpress.com/2012/03/25/the-education-of-an-eighteenth-century-squire-john-wilkes-1725-1797/

[1] Peter David Garner Thomas, John Wilkes: a Friend to Liberty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 2.

[2] Alexander Carlyle, Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of His Time (Cambridge, 1860), 168–69.

[3] Ibid., 138.

[4] James Boswell, The Journals of James Boswell: 1762-1795, ed. John Wain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 143–44.

[5] George Sebastian Rousseau, “‘In the House of Madame Vander Tasse’: A Homosocial University Club,” in Perilous Enlightenment: Pre- and Post-modern Discourses : Sexual, Historical, ed. George Sebastian Rousseau (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), 111–12.

[6] A Collection of Papers, Which Passed Between the Late Learned Mr. Leibnitz, and Dr. Clarke, in the Years 1715 and 1716 (London, 1717).

[7] Andrew Baxter, An Appendix to the First Part of The Enquiry into the Nature of the Human Soul (London, 1750), iii.

[8] John Almon, ed., The Correspondence of the Late John Wilkes: With His Friends, Printed from the Original Manuscripts, in Which Are Introduced Memoirs of His Life, 1805, 15; Arthur Hill Cash, John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty (Yale University Press, 2006), 14.

[9] Rousseau, “‘In the House of Madame Vander Tasse’: A Homosocial University Club,” 118.

[10] Jonathan Irvine Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650-1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002); Jonathan Irvine Israel, Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man, 1670-1752 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[11] Carlyle, Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, 167.

[12] Ibid., 166.

[13] Ibid., 167.

[14] Ibid., 171.

[15] D’Holbach to Wilkes, 9 August 1746, Max Pearson Cushing, Baron d’Holbach: a Study of Eighteenth Century Radicalism in France (Columbia University, 1914), 6.

[16] D’Holbach to Wilkes, 3 December 1746, Ibid., 10.