Category Archives: Art

The Public Reputation of the Medmenham Monks

How much did the London public know about the existence of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey during the 1750s and early 1760s? It is clear that its members had little reticence about publicizing their activities or worry about gossip and rumor. I have already posted about Francis Dashwood’s penchant for dressing up as monks and commissioning satirical religious portraits of himself (https://hellfiresecrets.wordpress.com/2012/03/02/francis-dashwood-portraiture-and-the-origins-of-the-hellfire-club/). It seems that he and his fellow members took great pleasure in encouraging gossip about their “secret” society.

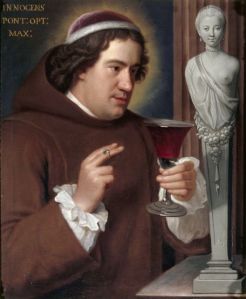

In one instance, Dashwood used his association with the Society of Dilettanti to publicize the group of “monks.” The Dilettanti required its members to present portraits of themselves to be hung in their meeting room, and the painter to the Dilettanti, George Knapton, painted Dashwood as “SAN FRANCESCO DE WYCOMBO” in 1742. Importantly, the Dilettanti’s meeting room was in a public tavern, and tavern-goers had access to it. In effect, the space became an informal art gallery. Because of this, a larger population came into regular contact with Dashwood’s image as St. Francis of Wycombe. The consequences of continuous public contact with Dashwood’s painting were described by John Wilkes. He said of Dashwood’s portrait, which had continuously hung at the King’s Arms from 1742 to 1757 before it was transferred to the society’s new home at the Star and Garter:[1]

In one instance, Dashwood used his association with the Society of Dilettanti to publicize the group of “monks.” The Dilettanti required its members to present portraits of themselves to be hung in their meeting room, and the painter to the Dilettanti, George Knapton, painted Dashwood as “SAN FRANCESCO DE WYCOMBO” in 1742. Importantly, the Dilettanti’s meeting room was in a public tavern, and tavern-goers had access to it. In effect, the space became an informal art gallery. Because of this, a larger population came into regular contact with Dashwood’s image as St. Francis of Wycombe. The consequences of continuous public contact with Dashwood’s painting were described by John Wilkes. He said of Dashwood’s portrait, which had continuously hung at the King’s Arms from 1742 to 1757 before it was transferred to the society’s new home at the Star and Garter:[1]

There was for many years in the great room, at the king’s arms tavern, in Old Palaceyard, an original picture of Sir Francis Dashwood, presented by himself to the Dilettanti club. He is in the habit of a Franciscan, kneeling before the Venus of Medicis, his gloating eyes fix’d, as in a trance, on what the modesty of nature seems most desirous to conceal, and a bumper in his hand, with the words MATRI SANCTORUM in capitals. The glory too, which till then had only encircled the sacred heads of our Saviour and the Apostles, is made to beam on that favourite spot, and seems to pierce the hallow’d gloom of maidenhead thicket. The public saw, and were for many years offended with so infamous a picture, yet it remain’d there, till that club left the house.[2]

Consequently, the lascivious and anti-religious connotations of this painting caused Londoners to confuse the activities of the Dilettanti with the private lives of its members. Even Horace Walpole, typically “in-the-know,” succumbed to conflating the Dilettanti and the “Order of St. Francis,” writing that Dashwood’s club was a “more select order” of Dilettanti:

These pictures were long exhibited in their club room in Palace Yard; but of later years St. Francis had instituted a more select order. He and some chosen friends had hired the ruins of Medmenham Abbey near Marlow.[3]

This confusion persisted throughout the 1760s and did much to link the Society of Dilettanti’s reputation to the Monks of Medmenham Abbey.

It seems that the “monks” of the Order of St. Francis were both cavalier about their activities and took pleasure in the notoriety – good and bad – that their excesses garnered. For example, Paul Whitehead’s membership in the Medmemnham Monks is one of the reasons that Boswell gives for Samuel Johnson’s dislike of the poet.[4] In 1762, John Wilkes was proud to claim that he had slighted (for a second time) William, Lord Talbot by postponing their duel because of a hangover that he had incurred at Medmenham. Writing to Richard Grenville, Earl Temple, on 6 October, the day after the duel actually took place, Wilkes wrote about his sarcastic exchange with Talbot.

I was come from Medmenham Abbey where the jovial monks of St. Francis had kept me up till four in the morning, that the world would therefore conclude I was drunk, and form no favourable opinion of his lordship from a duel at such a time.[5]

Temple’s response suggests familiarity with the group and that Wilkes’s behavior in this incident was a confirmation of his masculinity: “Firmness, coolness, and a manly politeness, makes up the whole of this transaction on your part . . . I was sure you would extricate yourself like a man.”[6]

Adapted from Jason M. Kelly, The Society of Dilettanti: Archaeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2009), chapter 2.

[1] The Society moved their room to the Star and Garter Tavern in May 1757. See SDSM, 1 May 1757.

[2] Reprinted in A Select Collection of the Most Interesting Letters on the Government, Liberty, and Constitution of England, vol. 2 (London, 1763), p. 37. This was an extension of [John Wilkes], Public Advertiser (2 June 2 1763).

[3] Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of King George III, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), p. 114.

[4] James Boswell, Life of Johnson, ed. R.W. Chapman (Oxford, 1980), p. 91.

[5] Wilkes to Temple, 6 October 1762 in Letters between Duke of Grafton . . . and John Wilkes, vol. 1 (London, 1769), pp. 22-3.

[6] Temple to Wilkes, 6 October 1762, Grenville Papers, vol. 1, p. 478.

A Nymphaeum and a Temple to Venus in an Eighteenth-Century English Garden

The Temple of Venus was one of the earliest features of West Wycombe’s gardens, which Sir Francis Dashwood began designing in the 1740s. It is a round temple, perched on a small hill. Below it was a section of the garden, known as Venus’ Parlor, which was cleared when Humphrey Repton re-landscaped West Wycombe beginning in 1796. As a consequence, Dashwood’s baroque figurative program for this section of the garden was destroyed. However, from remaining evidence, we can piece together what it looked like.

A view by William Hannan from the 1750s portrays the temple as it originally looked.

On a manmade hill, a circular temple – an allusion to the rotunda at Stowe but situated in gardens with a very different moral program – housed a copy of the Venus de Medici. A path led down the hill to a grotto built underneath the temple. A design for the grotto still exists in the Dashwood collections.

It appears that this section of the garden followed the design of a nymphaeum similar to those found in the gardens of Renaissance Italian villas. In effect, it is similar to Palladio’s nymphaeum for the Villa Barbara, although on a much smaller scale.

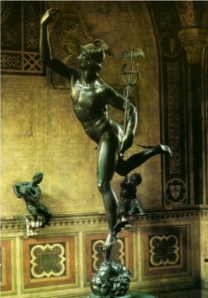

The oval entrance to the grotto alluded playfully to sexuality and temptation, with symbols that all but the most obtuse visitor could understand. Perched above the “door of life” – as John Wilkes later referred to it, was a lead copy of Giambologna’s sixteenth-century Mercurio – an iconic figure throughout the early modern period.[1] The lead Mercury can be seen in Hannan’s view. While Mercury’s association with commerce and communication are well known, eighteenth-century libertines often associated Mercury with sexual commerce as well.

While few textual descriptions of the site exist – and those that do are dubious descriptions – the tone of the site is embodied in John Wilkes’s description of West Wycombe. In 1763, he wrote that “you find at first what is called an error in limine; for the entrance to it is the same entrance by which we all come into the world, and the door is what some idle wits have called the door of life.”[2] He continued that Lord Bute had encouraged Dashwood to erect a Paphian column – a reference to the Temple of Venus at Paphos on Cyprus – in front of the entrance:

While few textual descriptions of the site exist – and those that do are dubious descriptions – the tone of the site is embodied in John Wilkes’s description of West Wycombe. In 1763, he wrote that “you find at first what is called an error in limine; for the entrance to it is the same entrance by which we all come into the world, and the door is what some idle wits have called the door of life.”[2] He continued that Lord Bute had encouraged Dashwood to erect a Paphian column – a reference to the Temple of Venus at Paphos on Cyprus – in front of the entrance:

There are in these gardens no busts of Socrates, Epaminondas, or Hampden [a reference to the Temple of Ancient Virtue and the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe]; but there is a most indecent statue of the unnatural satyr [the famed Satyr with a Goat in the King of Naples’ collection]; but at the temple I have mentioned, are two urns sacred to the Ephesian matron, and to Potiphar’s wife, with the inscriptions Matronae Ephesiae Cineres, Dominae Potiphar Cineres.[3]

The reference to the Ephesian matron was from Petronius’ Satyricon in which the chaste Matron Ephesia despairs at her husbands death and begins to starve herself in his tomb. Eventually, she is seduced by a soldier who brings her food. Potiphar’s wife was the woman who attempted to seduce Joseph in the biblical story. Thus, two of the most “sacred” items in the gardens were models of female infidelity.

It is no surprise that Repton cleared the site of its most explicit references to sexuality, libertinism, and anti-virtue in 1796. Likewise, it is perhaps not surprising that Dashwood’s descendants would commission a replica of the original grotto in the 1980s. By this time, West Wycombe had become an important National Trust Property – not only because of its architecture, but because of the ability of its illicit history to draw visitors. In 1982, Quinlan Terry completed his reconstruction of the grotto and temple for Sir Francis Dashwood. This commission was part of an overall plan to re-infuse the landscapes of West Wycombe with references to the world of the Hellfire Club, a draw for tourists which was meant to raise both the profile and income of the estate.

Citation: Jason M. Kelly, “A Nymphaeum and a Temple to Venus in an Eighteenth-Century English Garden,” Secrets of the Hellfire Club Blog (8 March 2012), https://hellfiresecrets.wordpress.com/2012/03/08/a-nymphaeum-and-a-temple-to-venus-in-an-eighteenth-century-english-garden/.

[1] Not only did Giambologna produce several copies himself (Museo del Bargello, Florence; Villa Medici, Rome; Museo Nazionale, Naples originally in Farnese collection; Kunsthistorisches, Vienna), but collectors such as Sir Hans Sloane and Lawrence Dundas added copies to their own collections. See, for example, Johann Zoffany’s Lawrence Dundas and Grandson in the Zetland Collection and Jeremy Warren, “Sir Hans Sloane as a Collector of Small Sculpture,” Apollo (2004): 8.

[2] New Foundling Hospital for Wit, vol. 3 (London, 1784), p. 78.

[3] New Foundling Hospital for Wit, vol. 3 (London, 1784), p.

Francis Dashwood, Portraiture, and the Origins of the Hellfire Club

The Monks of Medmenham Abbey, more popularly known as the Hellfire Club, were one of thousands of associational groups that formed in Britain and Ireland during the eighteenth century. During the 1750s and early 1760s, they met at the estate of Sir Francis Dashwood, a baronet whose family derived their wealth from trading silks in the Levant. Dashwood took numerous grand tours in the 1720s and 1730s, travelling to France and Italy, but also to Russia and the Ottoman Empire. He was well known for his interest in architecture and politics, as well as women and wine. And, like many of his fellow Britons, he had a particular fondness for masquerade, which found itself expressed through a penchant for dressing up as priests, monks, and popes.

Definitive proof of the group’s existence is not available until the 1750s. However, a variety of circumstantial evidence points to the origins of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey in the Grand Tour world of the 1730s and 40s. On his Grand Tour in 1740, Dashwood was signing letters to his friends as “St. Francis,” and in a letter to Lord Boyne, he noted that he longed “to make a party of Monks with you into the Country, remember that I am a Franciscan.”[1] He had travelled with Boyne on a tour to Italy in 1730-31, and it is possible that this was a reference to their earlier revelries on the continent.[2] But, in any case, it suggests that Dashwood was already holding parties where he dressed up as a friar as early as the 1730s. His letter to Boyne further indicated that he had composed a dozen songs for Lord Middlesex – perhaps the same songs that he performed a few weeks later in a mock conclave upon the death of Pope Clement XII. Written from Rome, this note to Boyne may be the first evidence of Dashwood’s interest in a creating a group in which members masqueraded as clergymen.

that Dashwood was already holding parties where he dressed up as a friar as early as the 1730s. His letter to Boyne further indicated that he had composed a dozen songs for Lord Middlesex – perhaps the same songs that he performed a few weeks later in a mock conclave upon the death of Pope Clement XII. Written from Rome, this note to Boyne may be the first evidence of Dashwood’s interest in a creating a group in which members masqueraded as clergymen.

In 1740, Charles de Brosses reported that Dashwood and William Matthias Stafford-Howard, 3rd Earl of Stafford – “mauvais catholiques” as he called them – caused a “vrai scandalum magnatum” by holding the mock conclave and impersonating Cardinal Ottoboni.[3] From “[c]e damné Huguenot” came a “repertoire de chansons libertines contre la papauté.” [4] A portrait – probably from the late 1730s or early 1740s – portrays Dashwood as a somber Franciscan friar. This is the first recorded evidence of him portraying himself as a member of the Roman Catholic church. In it, his left hand rests on a Bible next to a momento mori.

In 1742, Dashwood commissioned George Knapton to paint him as a Franciscan. It was one of over twenty portraits that Knapton completed for the Society of Dilettanti, which required its members to present Kit-Kat style paintings of themselves to the organization.[5] In a reference to his grand tour alter ego, Dashwood plays the role of SAN: FRANCESCO DI WYCOMBO. In his hands, he holds a goblet on which is inscribed the words MATRI SANCTORU[M] – “the mother of the saints.” The phrase had a double-entendre, referring, in part, to the metaphysical status of the Roman Catholic Church as mother of all Christians. On the other hand, the wine and the Venus de Medici reminded the viewer of the corporal world – of the senses, of desire and lust. It was the sexualized body of women that actually produced saints. To encourage this reading, Knapton removed the hand of the Venus revealing “the hallow’d gloom of maidenhead thicket” as John Wilkes would later describe it.[6] But, removing the hand of the Venus provided the viewer with another reading as well. At the time, there was much debate about the quality of craftsmanship on the statue’s extremities. Jonathan Richardson declaimed the fingers as “excessively long” with poor detail.[7] Removing the hand suggested that Dashwood had come to a similar conclusion, deciding that it was an inferior restoration. So, in addition to portraying himself as a libertine, Dashwood evoked his taste and knowledge of classical statuary.

In 1742, Dashwood commissioned George Knapton to paint him as a Franciscan. It was one of over twenty portraits that Knapton completed for the Society of Dilettanti, which required its members to present Kit-Kat style paintings of themselves to the organization.[5] In a reference to his grand tour alter ego, Dashwood plays the role of SAN: FRANCESCO DI WYCOMBO. In his hands, he holds a goblet on which is inscribed the words MATRI SANCTORU[M] – “the mother of the saints.” The phrase had a double-entendre, referring, in part, to the metaphysical status of the Roman Catholic Church as mother of all Christians. On the other hand, the wine and the Venus de Medici reminded the viewer of the corporal world – of the senses, of desire and lust. It was the sexualized body of women that actually produced saints. To encourage this reading, Knapton removed the hand of the Venus revealing “the hallow’d gloom of maidenhead thicket” as John Wilkes would later describe it.[6] But, removing the hand of the Venus provided the viewer with another reading as well. At the time, there was much debate about the quality of craftsmanship on the statue’s extremities. Jonathan Richardson declaimed the fingers as “excessively long” with poor detail.[7] Removing the hand suggested that Dashwood had come to a similar conclusion, deciding that it was an inferior restoration. So, in addition to portraying himself as a libertine, Dashwood evoked his taste and knowledge of classical statuary.

By 1745, evidence suggests that Dashwood may have been organizing a club at West Wycombe. George Bubb Dodington wrote to Dashwood about a small group that met at Dashwood’s residence, “I must confess, I never mett with more Improvement, as well as Entertainment, in so small a Company; & do verily believe, there are as many Sallies of true Witt, & Humour in Them, as most of the Societies in Town, which most pretend to Both can boast of.”[8]

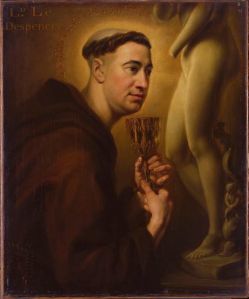

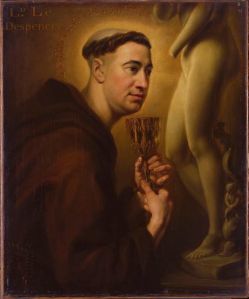

In the early 1750s, Dashwood once again commissioned a painter to represent him as a member of the clergy. Adrien Carpentiers showed Dashwood dressed as Pope Innocent III. He performs the act of transubstantiation next to a herm topped with the visage of his wife Sarah Ellys, described by Walpole as “a poor forlorn Presbyterian prude”[9] Her relationship with her rakish husband was no doubt strained. Two months before their wedding in 1745, Dashwood was writing to friends bragging that he was “employing 20 of the 24 hours wither upon [his] Belly, or from thence, like a Publick Reservoir, administering to those of other People, by laying [his] Cock in every private Family that has any Place fitt to receive it.”[10]

The first certain evidence of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey meeting comes from a letter from Richard Grenville, Earl Temple to Dashwood from October 1754. He refers to three other members of a club – a “wicked company” of John Wilkes, Paul Whitehead, and Sir George Lyttelton – who celebrated a “Love feast” and sat together at a “table of the Saints.” While the references are obscure, later documentation reveals that these were all members of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey and that the religious symbolism was used widely in their private writings and letters to each other. Earl Temple wrote to Dashwood,

It is very gracious and kind in the pious Aeneas, after his conversion, after the Love feast, to keep up that of friendship with one, who has so slender a claim to be admitted to the table of the Saints; but I am sorry to hear you are exalted to so high a story of faith and godliness, because great may be the fall thereof, and this Scotch taste of architecture is so contrary to the fashionable style of building in this country, that I fear it will never prevail, and that you will return to your humbler roof of mortality and every social virtue, with as much ardor, as if you had never deviated into the higher regions of cherubim and seraphim, or the conversion of [John] Wilkes, compared with that of St. Paul [Whitehead]; however, if I should live to see you in the bosom of our father Sir George [Lyttelton], I shall only now and then drink to the pious memory of the delightful moments I have passed in your wicked company, and begin to attach myself to all the interested pursuits of this world, as the sure road to a better.[11]

In 1757, Dashwood commissioned William Hogarth to mimic Knapton’s painting in yet another portrait as a member of the Roman Catholic clergy. Sir Francis Dashwood at His Devotions, modelled on Agostino Carracci’s St. Francis Adoring the Cross portrays him leering at a naked, prostrate woman. An open book, referring to the poems of Ovid, and a masquerade mask lie nearby as a tray of fruits and wine tumbles to the floor, referring the viewer to the excess of Carnival and the attendant rites of Bacchus and Venus. The nimbus over his head is the profile of his friend and fellow Medemenham Monk John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. This is a pivotal piece in the history of the group, one which will be the subject of future posts.

In 1757, Dashwood commissioned William Hogarth to mimic Knapton’s painting in yet another portrait as a member of the Roman Catholic clergy. Sir Francis Dashwood at His Devotions, modelled on Agostino Carracci’s St. Francis Adoring the Cross portrays him leering at a naked, prostrate woman. An open book, referring to the poems of Ovid, and a masquerade mask lie nearby as a tray of fruits and wine tumbles to the floor, referring the viewer to the excess of Carnival and the attendant rites of Bacchus and Venus. The nimbus over his head is the profile of his friend and fellow Medemenham Monk John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. This is a pivotal piece in the history of the group, one which will be the subject of future posts.

These early visual depictions and writings point to a decades-long development of the group. The association seems to have emerged from the male libertine sociability of the Grand Tour and the rage for masquerade that was such a feature of elite social life in the early eighteenth century.

[1] Dashwood to Boyne, 30 January 1740 NS, West Wycombe Archives, copy from an unidentified auction catalog in the West Wycombe Archives.

[2] Brinsley Ford and Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, A Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy, 1701-1800 / Ingamells, John. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1997), 278.

[3] Charles de Brosses, Lettres d’Italie du Président de Brosses, vol. 2 (Paris, 1986), 445.

[4] Charles de Brosses, Lettres d’Italie du Président de Brosses, vol. 2 (Paris, 1986), 445.

[5] Jason M. Kelly, The Society of Dilettanti: Archaeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2009), 37–56.

[6] Reprinted in A Select Collection of the Most Interesting Letters on the Government, Liberty, and Constitution of England, vol. 2 (London, 1763), p. 37. This was an extension of Public Advertiser, 2 June 1763.

[7] Jonathan Richardson, An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas-reliefs, Drawings and Pictures in Italy (London, 1722), 55.

[8] George Bubb Dodington to Dashwood, 5 October 1745, Bodleain MS D.D. Dashwood (Bucks) C.5 B11/1/5, 1r.

[9] Walpole, Corr., 19.224

[10] George Bubb Dodington to Francis Dashwood, 5 October 1745, Bodleain MS D.D. Dashwood (Bucks) C.5 B11/1/5. The marriage took place on 11 December 1757 according to Joseph L. Chester and George J. Armytage, Allegations for Marriage Licences Issued by the Bishop of London, 1520 to 1828, Harleian Society, vol. 26 (London, 1887), p. 345.

[11] Earl Temple to John Wilkes, 12 October 1754, The Grenville Papers: Being the Correspondence of Richard Grenville Earl Temple, K.G., and the Right Hon: George Grenville, vol. 1, ed. William James Smith (London: 1852), 125-7.

![[Anonymous]. Venus’ Parlor. ca. 1740s. Courtesy of Sir Edward Dashwood [Anonymous]. Venus’ Parlor. ca. 1740s. Courtesy of Sir Edward Dashwood](https://hellfiresecrets.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/grotto.png?w=490&h=354)